…and I am happily peacefully and dangerously writing a book now 🙂

Start Date: Oct 1991 – Present

This is what it’s about…

To the people who have known me and secretly wondered,

“Why is she like that?” —

this is the long, honest answer.

And to the people who haven’t met me yet:

this is really about YOU.

Because the question behind every life is the same —

“Why am I like this?

A Sneak Peek

I’m currently editing the book and working on the illustrations.

It will likely take another two months before it’s ready.

If you’re curious, I’m sharing the first two chapters below—unedited, as they are.

——

Oct 7th, 1991

I was born at home – my grandparents’ home

PART I – THE FOUNDATIONS

BEFORE I KNEW MYSELF

Where the nervous system learned its first language

CHAPTER 1: The Kid Who Accidentally Managed the Whole Family

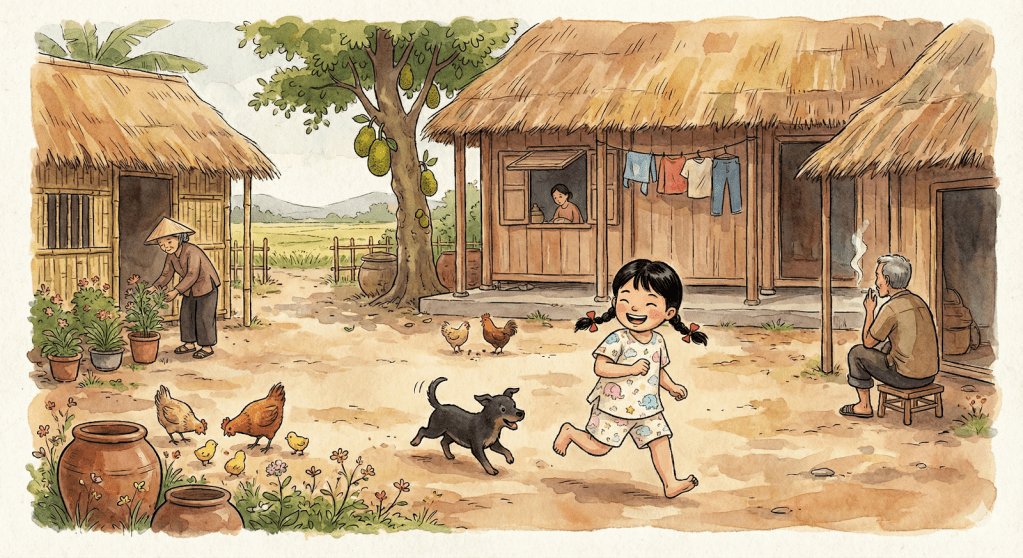

I grew up in a family where the biggest luxury wasn’t money, it was space.

Not emotional space (absolutely none of that).

Not personal space (nonexistent), but literal, physical square meters.

We were poor, but we had three houses:

- Grandma’s house: a tiny wooden kingdom where she ruled with perfectionism and grass threads, weaving sleeping mats from strands so fine they felt like the quiet strength of a woman who had survived too much, and kept going anyway.

- Grandpa’s house: 20 meters away, his personal “I’m done with your grandma” sanctuary.

- The middle house: where my aunts, my uncle, and I all lived like one noisy ecosystem.

Three houses, but if someone coughed in one, the other two heard it.

Walls were made of wood, coconut leaves, and hope.

Doors had no locks—not because we trusted people, but because there was nothing worth stealing.

I was the happiest kid running between these houses… completely unaware that I had already become the family mediator, the emotional courier, the unofficial United Nations peacekeeper, and the complaint handling specialist.

The Family Complaint Network (Quantum Edition)

And talking about complaints…

My aunts complained about each other.

My uncle complained about my grandma.

Grandpa complained about my uncle.

My grandma complained about all of them.

And my…

Actually, let’s just say:

If quantum physics ever needed a model of infinite permutations, they could study my family arguments. But one thing never changed:

NO ONE ever shouted at me. They only came to ME to share.

I was the safe zone.

The emotional Switzerland.

The tiny Buddha without the wisdom.

The kid who didn’t know she was keeping the family together… simply by listening.

What I Know Now

Back then? I thought it was normal.

Now I see it clearly: I wasn’t just a kid running between houses.

I was the bridge between people who loved each other, feared each other, misunderstood each other, and couldn’t say “I’m sorry” even if their life depended on it.

Every family has someone like this.

A person who absorbs the chaos and turns it into connection.

A stabilizer.

A listener.

A soft landing.

A translator of feelings adults don’t know how to express.

Some families call them “the responsible one.”

Some call them “the old soul.”

Some don’t even notice them at all.

But here’s the truth: If you were the child who kept the peace, you were never weak.

You were never too emotional.

You were never “mature for your age.”

You were the emotional architect of a home that didn’t know how to hold itself together.

And that is not a burden.

It is a gift.

One you learned too early, but one that now, finally, belongs to you.

I thought I was just a kid running between three small houses.

But I was actually carrying an entire family across the distance between their hearts.

——

CHAPTER 2: Grandma — The Original Perfectionist

(who unintentionally trained another one)

My grandma ran a handmade workshop—the best in town.

She was a perfectionist long before the word ever trended on Instagram. She made sleeping mats from grass threads. And shopping bags, too. The same kind of bags you now see repurposed in luxury boutiques and tropical hotels.

I often think: if someone had discovered her talent at the right time, we might have been famous. Or at least… less poor.

She couldn’t read. She couldn’t write. But she was sharp. She never missed a deadline. If someone ordered something, she remembered every detail and delivered it exactly on the day she promised.

Never late. Not once.

She was also a quiet investor. Whenever she saved enough money for a small gold ring, she rushed to the market and bought one. Gold didn’t lose value. Gold was safety.

Her dream was simple: to build a brick house. That dream came true when I was thirteen. If it hadn’t been for my school fees and extra classes, it might have happened earlier.

But I know—deep down—my little certificates built her several brick houses or maybe castles in her heart. I was trying to build a whole dynasty for her.

Making mats was slow, precise work. Every single thread had to be inspected and matched in size so the final pattern would look neat and even. One sleeping mat—160 by 200 centimeters —took an entire day. From five or six in the morning until eight or nine at night.

My grandma and my Aunt Ten were the master artisans.

And me? I was the grumpy assistant.

I started helping when I was seven or eight.

And yes—that’s exactly where my eye for detail comes from.

“Hate” is a strong word. But I definitely used it for her workshop.

Whenever she asked me to help, I lied:

“Con có bài tập về nhà.” (I have a lot of homework today.)

She always knew I was lying.

Always.

But because it involved “studying,” she let the lie live.

That was her love language: strictness paired with silent permission.

She complained constantly that girls didn’t need too much education.

“You’ll grow up, get married, and leave. Why study so much?”

She would say that in the morning.

At night, she would add:

“If you don’t get good grades, I’ll send you to the market to sell lottery tickets. So study well.”

Contradictions were her specialty.

When I was seven, she sent me to a pagoda to learn Chinese. The same woman who said we couldn’t afford my education was also the one paying my tuition.

Every time I announced it was time to pay the fee, she would sigh:

“Only one more month, okay?”

And just like that, I continued until I was fifteen.

I earned my C-level certificate for Chinese—Advanced Level.

Chinese classes started at six in the evening. I walked to the pagoda at five. When lessons ended two hours later, I stood at the gate and waited.

There were no street lights back then. My grandma would come with an oil lamp. I followed her small silhouette home in silence.

Love was warm.

That’s how I never missed a lesson.

She was funny, too—in her own way.

She was everything to me: my mother, my teacher, my Marcus Aurelius, my dentist, my doctor.

I rarely went to hospitals.

She diagnosed everything herself and always knew exactly what herb, oil, or remedy to find.

Once, I had a severe seafood allergy. I drank water nonstop and swelled up so much I nearly doubled in size. All night, she sat beside me, fanning me, giving me water.

Moments like that get recorded by the body immediately. Later in life, your body recognizes this kind of love again—and it also recognizes the absence of it.

By morning, I was fine.

My grandma didn’t believe in allergies. No one in our family had them. So she concluded I simply wasn’t resilient enough. She kept feeding me seafood—smaller doses. I kept reacting.

Until one day… I didn’t. Now the only allergy I have is bad food.

She complained a lot.

But she forgave easily.

During the war in the 1960s, a bomb fell on the bunker. Her kneecap was destroyed. It never healed. She told me stories about the hospital—how kindly the American nurses treated her, how it was the first time she ever saw canned food. She didn’t hate them.

She could be sharp with words, but she broke easily inside. That’s how I learned to question criticism:

Is this about me—or about someone trying to protect themselves?

If anything, my grandma taught me this:

Love doesn’t need to be spoken. It works harder than words.

….

If these stories resonate with you and you’d like to read the book when it’s finished, you can leave your contact here.

I’ll send it to you when it’s ready.